Introduction:

In May 2021 the Danish Parliament agreed to a government proposal to deploy a Danish combat vessel to the deeply troubled Gulf of Guinea on a special mission to patrol the waters and protect Danish and other merchant vessels that sail within the region from pirates. Denmark has significant maritime interests within the Gulf of Guinea region, with an estimated 30-40 Danish flagged or controlled merchant ships traversing its terrifying waters.

On 24th October, the frigate HDMS Esberne Snare left the Danish Naval Base Frederikshavn for West Africa with a contingent of military police, a helicopter and special operations forces.2 Exactly a month later, the warship received reports of a suspected attack on a merchant ship and immediately sailed towards that direction. The frigate’s seahawk helicopter was dispatched to survey the situation, and it reported sighting a speeding motorboat with eight suspicious men aboard with tools and materials used by pirates on board. When the warship got close enough, it called upon the pirate ship to stop for boarding and inspection, and proceeded to fire a warning shot when the pirates ignored the order. The pirates fired directly onto the Danish soldiers, provoking a brief gun battle that resulted in the death of 4 suspected pirates, the wounding of one and the arrest and detention of the remaining three.

The wounded pirate, a Nigerian national, was sent to a hospital in Ghana for medical care that resulted in the amputation of one of his legs whilst the three others were sent to Copenhagen. They were charged and stood trial for the offence of “attempted murder of Danish soldiers.” Sadly however, the Danish court declined jurisdiction, and the captured suspected pirates had to be set free upon the same waters they caused terror without answering for their crimes, and immediately put out to sea on a dingy.

The wounded pirate, a Nigerian national, was sent to a hospital in Ghana for medical care that resulted in the amputation of one of his legs whilst the three others were sent to Copenhagen. They were charged and stood trial for the offence of “attempted murder of Danish soldiers.” Sadly however, the Danish court declined jurisdiction, and the captured suspected pirates had to be set free upon the same waters they caused terror without answering for their crimes, and immediately put out to sea on a dingy.

This is due in part to the fact that the Danish government could not find any country along the Gulf of Guinea which was willing to accept and trial the suspected pirates. This incident marked an important milestone in the evolution of the region’s counterpiracy operations as it was the first time suspected pirates had been killed by an international Naval vessel operating within the region.3

Conceptualizing Piracy:

Piracy has its provenance in antiquity. It is coeval with sea navigation itself. As was observed by a judge of the International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea, “the very first time something valuable was known to be leaving a beach on a raft the first pirate was around to steal it.” As early as 75 BC, a young Julius Caesar was captured by pirates and held for ransom. At its most basic level, Piracy may be conceived as “armed robbery at sea”. Indeed, this was for a considerable time the prevailing definition of piracy. Sir Charles Hedges whilst charging the grand jury in the Dawson’s Trial at the Old Bailey in 1696, remarked that “piracy is only a sea-term for robbery, piracy being a robbery committed within the jurisdiction of the Admiralty”.6

In the United States v Smith7 decided by the United States Supreme Court in 1820, Sir Justice Story observed thus; “whatever may be the diversity of definitions, all writers concur, in holding, that robbery or forcible depredations, animo furandi, upon the sea… is piracy … Whether we advert to writers on the common law or the maritime law, or the law of nations, we shall find that they universally treat piracy as an offense against the law of nations, and that its true definition by that law is robbery upon the sea.”

The current definition of piracy under international law, is however more expansive in scope and effect than the above. The 1992 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (LOSC) contains provisions on piracy in articles 100 to 107; and 110. The Convention defines piracy as any illegal act(s) of violence or detention or depredation committed for private ends by crew or passengers of a private ship or aircraft, against a ship or aircraft, persons, or property on the high seas, or any act of voluntary participation in the above or any act of inciting or intentionally facilitating any acts described above. This definition raises a number of implications. First, there must be an illegal act of violence or detention or depredation, and this may be committed against a ship/aircraft as a unit or its occupants or other property on board.

Secondly, such illegal acts must be committed for “private ends”. This phrase raises difficulties. For example, does “private ends” entail politically or ideologically motivated acts like ecological activism at sea by Greenpeace activists”? Two views exist as to what constitutes private ends; the first is that any illegal acts of violence for political reasons are excluded; and secondly, all acts of violence that lack state sanction or authority are acts for private ends.

The Santa Maria Affair offers some illustration on this point; In 1961, a Portuguese ship was taken over by a Portuguese political dissident, who declared that the seizure was a first step to overthrow the Dictator, Salazar of Portugal. The Flag State, Portugal designated the seizure an act of piracy but the offender sought and obtained asylum from his followers in Brazil. Clearly, there was no state sanction of this act, hence it would be for private ends going by the second school of thought.

In the 1986 case of The Castle John v Babeco, Greenpeace activists took action against two Dutch vessels engaged in illegal discharge of toxic waste into the sea, which involved boarding, occupying and causing damage to the ships with a view to attracting public awareness. The Belgian Court of Cessation held that these were for private ends. A similar incident involved the Institute of Catecian Research v Sea Shepherd Conservation Society9, where the defendants harassed a Japanese whaling fleet. The United States Court of Appeal held that this was clearly an act of violence committed for private ends, and the fact that the protesters believed they were serving a public good did not render their acts “public”. (See also the Arctic Sunrise case between Holland and Russia).

Thirdly, piracy must be committed by the crew or passengers of a private ship or aircraft against another ship or aircraft; persons or property aboard it. There must be two vessels, the pirate vessel and the victim, and the former must necessarily be private. Thus, piracy cannot be committed by a warship or government ship/aircraft unless the crew have mutinied and taken control of the vessel to perpetrate violent acts against another vessel.. The requirement of duality of ships is best illustrated by the Achille Lauro Affair, where members of a Palestinian group boarded an Italian Passenger ship disguised as passengers and hijacked the ship later. They demanded the release of some Palestinian prisoners, and in the process, a disabled American citizen was brutally killed. As the offenders were not passengers of another vessel but the victim vessel itself, the act did not constitute piracy within the meaning of the Convention.

The fourth definitional requirement of piracy is that, it must be committed on the high seas or an area outside the sovereignty of any state. By virtue of the cross-reference provision in article 58(2) LOSC to its provisions on the high seas (i.e. articles 86-115), piracy can take place within the EEZ. The English law decision in Republic of Bolivia v Indemnity Mutual Assurance applied this principle when it held that an attack by war insurgents upon the Amazon river, did not constitute piracy. This is because inland/internal waters constitute part of the territory of the state within which they flow.

Piracy & Universal Jurisdiction:

Jurisdiction is understood to mean “the extent of each state’s right to regulate conduct or the consequence of events, and the legal competence of a state…to make, apply and enforce rules of conduct upon persons.” This implies the state’s authority to enact laws (prescriptive jurisdiction) and to enforce their compliance (enforcement jurisdiction). The default basis for the exercise criminal jurisdiction by states is the territorial principle, which underlies the state’s competence to prescribe, adjudicate and enforce its penal laws over its own territory.

Exceptionally, international law affords states limited extra-territorial bases for exercising jurisdiction, as are necessary to protect their sovereign interests as well as to control and protect their nationals. The nationality principle for instance, allows states to exercise criminal jurisdiction over their nationals abroad. States may also exercise jurisdiction over conduct by foreign nationals outside of their own territory, if the said conduct affects its nationals outside of its territory (“passive nationality principle”). Furthermore, a state may exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction if the offence is directed against a critical national interest of the state (“protective principle”).

The other basis for exercising extra-territorial jurisdiction apart from those identified above, is the “universality principle.” Whilst the nationality principle, the passive nationality principle and protective principle all maintain some necessary nexus between the offence and the state seeking to exercise jurisdiction, the universality principle has no such requirement for a direct connection. Under this principle, a state is permitted by international law to prosecute and punish offenders for a class of offences recognized by the community of nations as posing a universal concern, without regard to territoriality or nationality. The characterization of some offences as international crimes, or what a writer refers to as jus cogens offences reflects the extreme revulsion and reprobation held of such offences by the international community. This is indeed predicated upon the notion that such crimes are so abhorrent that their very nature jeopardizes the interests of all humanity, and in fact, imperils civilization itself18. Bassiouni proceeds to identify the following to be examples of jus cogens offences; aggression, genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, piracy, slavery and slave-related practices and torture.19 He argues further that the characterization of these offences as international/jus cogens crimes do not just imply a universal jurisdiction to arrest and punish, but a peremptory duty upon all nations to arrest, try and punish such offenders; an obligations erga omnes arising by virtue of customary international law.

Piracy constitutes a quintessential example of universal jurisdiction. It has long been considered, indeed, to be the “grandfather” of all universal crimes.20 Judge Guillaume noted in the Arrest Warrant case21 that customary law knows of only one true case of universal jurisdiction; piracy. Pirates are thus international criminals, and may be captured by the authorized agents of any recognized state, subjected to its criminal jurisdiction and punished according to its local laws.22 Some of the reasons for characterizing pirates as international criminals, subject to universal jurisdiction under the law of nations are discussed as follows;

Mare Liberum and the Common Heritage of Mankind:

Firstly, unlike land-based banditry which is subject to the jurisdiction of the state of occurrence or nationality of its victims, pirates are marauders who prowl upon the high seas for vessels to attack and plunder indiscriminately, without recourse to their nationality. Since the early 17th Century when Grotius published the Mare Libervm, the principle of the open seas has been the dominant rule concerning the use of the sea. This principle underscores the notion that the sea, both as a whole and in its constituent divisions, cannot be subject to private ownership. In modern international law, the coastal states have the right to appropriate up to 12 nautical miles of coastal waters, and establish an exclusive economic zone of up to 200 nautical miles from the baseline along the coast. The coastal zone beyond these waters constitute the high seas, the locus of maritime piracy. Being nullius territorium, no governmental authority extends onto the high seas. It is res communis, i.e. open to all mankind, and possessed by none. It forms a substantial part of the global commons. There is therefore a universal interest in the prompt arrest and punishment of pirates, due to the locus of their operations and their effects on mankind. This universal interest constitutes an important basis for the concept of universal jurisdiction, which allows all states to arrest and punish pirates without regard to the nationality of the pirates or their victims.

Pirates as Hostis Humani Generis:

There is a universally-held view that pirates are common enemies of all mankind, hostis humani generis. Cicero, the great Roman scholar wrote that “…a pirate is not included in the list of lawful enemies, but is the common enemy of all; among pirates and other men, there ought be neither mutual faith nor binding oath.” The evident revulsion in Cicero’s denunciation of pirates stems not just from the heinousness of piratical attacks per se. More heinous offences are committed by brigands, thieves and murderers on land. What appears to gall Cicero about piracy, however, is the fact that these acts are committed at sea – an element of nature that is not the natural habitat for mankind. Seafaring has always been a treacherous venture in and of itself. At sea and in the air, men are deemed to be at their most vulnerable state since they are not upon their natural environment-terra firma. It is practically impossible to escape from a ship at sea or from a plane in the skies without a risk of predictable death or serious injuries, at best. This is why international law imposes a moral duty upon all nations and persons at sea to assist anyone in distress at sea.

The intrinsic perils of sea navigation and the heightened vulnerability of men at sea makes it the more objectionable to purposely attack and endanger seafarers with the aim of plundering their possessions. The idea of saving lives and property at sea is diametrically opposed to deliberate acts of depredation, murder and plunder at sea. This is what makes the offence of piracy particularly revolting. Furthermore, the indiscriminate nature of piracy attacks equates to waging of war on all countries. Also, attacks on commercial vessels disrupt international trade in general. This reality was echoed by the court in Rex v Dawson25 when it observed thus; “Suffer pirates, and the commerce of the world must cease.” A disruption in international commerce affects all nations in the world, hence there is a universal interest in curtailing the scourge of maritime piracy.

The intrinsic perils of sea navigation and the heightened vulnerability of men at sea makes it the more objectionable to purposely attack and endanger seafarers with the aim of plundering their possessions. The idea of saving lives and property at sea is diametrically opposed to deliberate acts of depredation, murder and plunder at sea. This is what makes the offence of piracy particularly revolting. Furthermore, the indiscriminate nature of piracy attacks equates to waging of war on all countries. Also, attacks on commercial vessels disrupt international trade in general. This reality was echoed by the court in Rex v Dawson25 when it observed thus; “Suffer pirates, and the commerce of the world must cease.” A disruption in international commerce affects all nations in the world, hence there is a universal interest in curtailing the scourge of maritime piracy.

Statelessness

Another basis for the exercise of universal jurisdiction over piracy, is that by their conduct, both the pirates and their ships are rendered stateless. Modern international law makes it mandatory for every seagoing ship to be registered in one state or another. The vessel automatically assumes the nationality of the state and becomes entitled to fly its flag. The vessel also becomes subject to the jurisdiction and regulatory control of the flag state, and enjoys its protection in much the same way as its natural citizens. Thus, on the high seas, where no national laws exist in whatever form, the concept of flag state jurisdiction applies exclusively to regulate vessels and maintain maritime order. The underlying assumption for the exclusivity of flag state jurisdiction, is that the ship is an extension of the territory of the flag state.27 An unregistered ship is considered to be stateless, and enjoys no protection from any state.28 This principle was confirmed by the Privy Council in the Asya29, where Lord Simonds remarked that “the freedom of the open sea…is a freedom of ships which fly, and are entitled to fly, the flag of a state.” Some jurists like Blackstone, argue that, as enemies of all mankind, pirates are denuded of their nationality, and thereby become subject to the jurisdiction of every state.30

According to him, the crime of piracy is an offence against the universal law of society: a pirate being, according to Sir Edward Coke, hostis humani generis [enemy to mankind]. As therefore he has renounced all the benefits of society and government, and has reduced himself afresh to the savage state of nature, by declaring war against all mankind, all mankind must declare war against him: so that every community has a right, by the rule of self-defense, to inflict that punishment upon him which every individual would in a state of nature have been otherwise entitled to do, any invasion of his person or personal property.”

Modern conception of international law, however, no longer supports this view. The LOSC now makes it clear that a pirate ship does not automatically lose its nationality. Instead, it leaves it to the discretion of the flag state, whether the pirate ship will retain its nationality or not. The Convention nonetheless, emphasizes that every state may seize a pirate ship or any other ship under the control of pirates and detain the occupants on the high seas or in any other place outside national jurisdiction.

Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea (GoG):

The coast of the GoG abuts the territories of 17 African countries: Benin, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Gabon, Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Togo and the archipelago of Sao Tome and Principe. Angola and the Republic of the Congo lie south, with Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, the Gambia and Senegal to the north. With a combined gross domestic product (GDP) of $866.343 billion as of 2021.

These countries account for approximately 45% of the GDP of Sub-Saharan Africa. The GoG region contains vast reserves of hydrocarbon, fisheries and mineral resources that contribute significantly to the national revenues of the adjoining coastal states. The region also constitutes an important shipping zone for international trade between Europe and Asia. Furthermore, it accounts for about 25% of Africa’s maritime traffic with about 1000 merchant and fishing vessels crisscrossing the nearly 20 commercial seaports along its coastline every day. The region also provides two-thirds of Africa’s oil production and holds up to 4.5% of the world’s proven oil reserves, and 2.7 of proven natural gas reserves.35 Currently, countries like France, Italy and the United Kingdom have significant investments in oil and gas exploration within the region. It is self-evident, therefore, that the requirement for peace and security within the GoG region, is not just a concern for the coastal states, but also for the wider international community in general. With the signing and operationalization of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), there is an even greater need to maintain security in the region for a more effective continental integration and continent-wide economic prosperity.

These countries account for approximately 45% of the GDP of Sub-Saharan Africa. The GoG region contains vast reserves of hydrocarbon, fisheries and mineral resources that contribute significantly to the national revenues of the adjoining coastal states. The region also constitutes an important shipping zone for international trade between Europe and Asia. Furthermore, it accounts for about 25% of Africa’s maritime traffic with about 1000 merchant and fishing vessels crisscrossing the nearly 20 commercial seaports along its coastline every day. The region also provides two-thirds of Africa’s oil production and holds up to 4.5% of the world’s proven oil reserves, and 2.7 of proven natural gas reserves.35 Currently, countries like France, Italy and the United Kingdom have significant investments in oil and gas exploration within the region. It is self-evident, therefore, that the requirement for peace and security within the GoG region, is not just a concern for the coastal states, but also for the wider international community in general. With the signing and operationalization of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), there is an even greater need to maintain security in the region for a more effective continental integration and continent-wide economic prosperity.

Maritime insecurity in the GoG is exemplified by a cocktail of criminal activities at sea. Foremost among these “blue crimes” are piracy and armed robbery at sea. The region has historically had its own share of piracy incidents, but these did not constitute major global threats until recent years. Data from the International Maritime Organization (IMO) shows that armed attacks in the GoG increased from 23 in 2005 to 60 in 2007, and slightly declined until the mid 2010’s when it started gaining attention at the regional and international levels as a piracy hotspot, comparable to the scourge in the Somali coast. By 2012, the alarming surge in armed attacks, vessel boarding and hijacking, kidnapping and murder of seafarers had made the GoG the number one hotspot for maritime piracy in the world. In fact, it was reported that more seafarers were attacked in the GoG than along the Somali coast in the year 2012.

Maritime insecurity in the GoG is exemplified by a cocktail of criminal activities at sea. Foremost among these “blue crimes” are piracy and armed robbery at sea. The region has historically had its own share of piracy incidents, but these did not constitute major global threats until recent years. Data from the International Maritime Organization (IMO) shows that armed attacks in the GoG increased from 23 in 2005 to 60 in 2007, and slightly declined until the mid 2010’s when it started gaining attention at the regional and international levels as a piracy hotspot, comparable to the scourge in the Somali coast. By 2012, the alarming surge in armed attacks, vessel boarding and hijacking, kidnapping and murder of seafarers had made the GoG the number one hotspot for maritime piracy in the world. In fact, it was reported that more seafarers were attacked in the GoG than along the Somali coast in the year 2012.

Of the 191 cases of piracy attacks that were reported in 2016, 47 occurred within the GoG. In 2018 the number increased to 74 cases out of a total of 201 cases reported worldwide. In 2020, 130 maritime kidnappings were recorded in the GoG out of 135 cases worldwide, being the highest ever recorded in the region. A previous high was reached in 2019 when 121 seafarers where abducted. In the first four months of 2021 alone, a total of 40 kidnapping incidents were recorded worldwide, all in the GoG. It is estimated that the direct and indirect costs of maritime crime in the GoG amount to at least $2 billion. The GoG piracy situation has been attributed to institutional breakdown, systemic corruption, ineffective governance and activities of militant groups in the region, especially the Niger Delta area.

Of the 191 cases of piracy attacks that were reported in 2016, 47 occurred within the GoG. In 2018 the number increased to 74 cases out of a total of 201 cases reported worldwide. In 2020, 130 maritime kidnappings were recorded in the GoG out of 135 cases worldwide, being the highest ever recorded in the region. A previous high was reached in 2019 when 121 seafarers where abducted. In the first four months of 2021 alone, a total of 40 kidnapping incidents were recorded worldwide, all in the GoG. It is estimated that the direct and indirect costs of maritime crime in the GoG amount to at least $2 billion. The GoG piracy situation has been attributed to institutional breakdown, systemic corruption, ineffective governance and activities of militant groups in the region, especially the Niger Delta area.

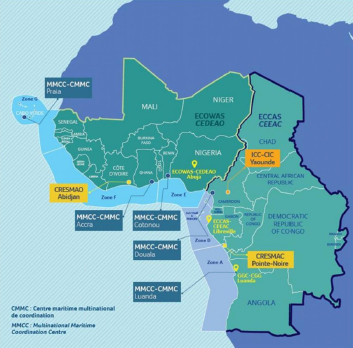

In view of the rising insecurity at sea, African countries in West and Central Africa bordering the GoG, engaged in collaborated efforts to contain the situation, which culminated with the Yaoundé Code of Conduct in 2013, aimed at achieving sustained cooperation, information and intelligence sharing. The international community has also been supportive in the fight for security in the GoG. The United Nations Security Council adopted UNSC Resolutions 2018 in 2011 and 2039 in 2012 respectively, on maritime piracy in the GoG.

In view of the rising insecurity at sea, African countries in West and Central Africa bordering the GoG, engaged in collaborated efforts to contain the situation, which culminated with the Yaoundé Code of Conduct in 2013, aimed at achieving sustained cooperation, information and intelligence sharing. The international community has also been supportive in the fight for security in the GoG. The United Nations Security Council adopted UNSC Resolutions 2018 in 2011 and 2039 in 2012 respectively, on maritime piracy in the GoG.

At its meeting on 31st May 2022, Ghana and Norway co-authored a draft resolution on maritime security in the GoG to the Security Council for consideration, which was adopted as Resolution 2634 (2022). These resolutions have rallied international support for regional efforts in reversing the tides of maritime insecurity in the GoG. Consequently, several nations including France, Denmark, the UK, Brazil, the USA and Spain have contributed to bilateral partnerships in this regard.

Since April 2021, the GoG started to experience a sharp decline in the rate of piratical attacks after it reached a crescendo in 2020 and the first quarter of 2021. There was no recorded incident of a successful attack in the region in 2022, though as many as 12 attempts were reported within the first half of the year. This welcoming development arguably evidences the apparent potency of the counter-piracy measures that have been deployed so far. The heavy presence of naval vessels within the region accounts in large part, for this development. But this is by no means a cause to relax just yet. A recent report by the European Commission shows a sharp increase in oil theft and illegal bunkering activities in the Niger Delta enclave, amidst a surge in riverine piracy.

Since April 2021, the GoG started to experience a sharp decline in the rate of piratical attacks after it reached a crescendo in 2020 and the first quarter of 2021. There was no recorded incident of a successful attack in the region in 2022, though as many as 12 attempts were reported within the first half of the year. This welcoming development arguably evidences the apparent potency of the counter-piracy measures that have been deployed so far. The heavy presence of naval vessels within the region accounts in large part, for this development. But this is by no means a cause to relax just yet. A recent report by the European Commission shows a sharp increase in oil theft and illegal bunkering activities in the Niger Delta enclave, amidst a surge in riverine piracy.

The report further suggests that the same actors involved in deep-sea piracy in the region, have shifted their attention to what they consider now to be more lucrative and less risky operations. If this is indeed so, it means then, that the root cause of GoG piracy is still intact, and the risk of resurgence or relapse is still real. If the foregoing is true, it means that the presence of heavily armed naval patrol boats has deterred Gulf of Guinea pirates, who have now shifted the focus of their operations elsewhere. The unavoidable implication is that the threat is still there, and there can be a resurge anytime we let our guards down.

Conclusion:

In view of the foregoing disquisition, there is the need for littoral states to devise ingenious and sustainable on-shore measures to complement off-shore naval patrols. More particularly, GoG nations ought to align their penal statutes with the modern definition of piracy under international law, and retool their judicial and prisons systems to engender efficient and expeditious trial and punishment of pirates captured at sea. In essence, Gulf of Guinea states must own the counterpiracy architecture in the region, and not just rely almost entirely on international support.

If the Esberne Snare incident recounted supra teaches us anything, it is the fact that foreign assistance can go only so much. After apprehending pirates in West African waters and sending them to Denmark, the Danish government ended up releasing them back to sea to resume their terrifying activities. This is a poignant reminder that GoG maritime insecurity is principally a West African problem, which must be tackled by West African states with efficient home-grown measures whilst utilizing as efficiently as possible, whatever support the international community may avail to us.

By: Kwesi Fokuor-Benyin