Background

Blue Economy has become a t erm that relates to the exploitation of the marine environment for sustainable development. It has become very necessary for global leaders, businesses, governments and individuals to recognize the essence of conserving the marine environment and also maximize its potential. The ocean are not only a primary food source for coastal communities and islands, but an intricate part of many economies and impacts every aspect of the environment cycle of life. The Blue Economy is essential to livelihood and food security of billions of people around the globe and thus at its core, must be sustained. The Blue Economy concept seeks to promote economic growth, social inclusion, and the preservation or improvement of livelihoods while at the same time ensuring environmental sustainability of the ocean and coastal areas. 02 OCTOBER – DECEMBER, 2023.

The need for the sustainability of the marine and its habitats stems from the fact that resources from the ocean is limited and the general health of the ocean is declining. This has in a marginal scale affected the livelihood of people. It has further been realized that human interactions with the ocean are causing more harm to the health of the ocean even though the ocean does not only support its habitats. For example, close to 70% of Indonesia’s population lives on the coastline and depends on it, but unfortunately, the country is the second largest producer of plastic waste after China. This and many other views like the projected growth of its population are likely to impact the ocean adversely. The Blue Economy is an all encompassing economy with diverse components, including ocean industries such as fisheries, tourism, and maritime transport, and also the new and emerging activities, such as offshore renewable energy, aquaculture, seabed extractive activities, and many more to be considered. A number of services provided by the ocean also exist which do not have markets yet, but also contribute significantly to economic and other human activities.

The need for the sustainability of the marine and its habitats stems from the fact that resources from the ocean is limited and the general health of the ocean is declining. This has in a marginal scale affected the livelihood of people. It has further been realized that human interactions with the ocean are causing more harm to the health of the ocean even though the ocean does not only support its habitats. For example, close to 70% of Indonesia’s population lives on the coastline and depends on it, but unfortunately, the country is the second largest producer of plastic waste after China. This and many other views like the projected growth of its population are likely to impact the ocean adversely. The Blue Economy is an all encompassing economy with diverse components, including ocean industries such as fisheries, tourism, and maritime transport, and also the new and emerging activities, such as offshore renewable energy, aquaculture, seabed extractive activities, and many more to be considered. A number of services provided by the ocean also exist which do not have markets yet, but also contribute significantly to economic and other human activities.

Some of these include carbon sequestration, coastal protection, waste disposal and the existence of biodiversity. Components of the Blue Economy The various activities in and around the environs of the ocean vary from country to country, depending on their unique national circumstances and the national vision adopted to reflect its own conception of a Blue Economy. In order for a particular activity to qualify as a component of a Blue Economy, such activity needs to: provide social and economic benefits for current and future generations restore, protect, and maintain the diversity, productivity, resilience, core functions, and intrinsic value of marine ecosystems. b e based on clean technologies, renewable energy, and circular material flows that will reduce waste and promote recycling of materials.

Some of these include carbon sequestration, coastal protection, waste disposal and the existence of biodiversity. Components of the Blue Economy The various activities in and around the environs of the ocean vary from country to country, depending on their unique national circumstances and the national vision adopted to reflect its own conception of a Blue Economy. In order for a particular activity to qualify as a component of a Blue Economy, such activity needs to: provide social and economic benefits for current and future generations restore, protect, and maintain the diversity, productivity, resilience, core functions, and intrinsic value of marine ecosystems. b e based on clean technologies, renewable energy, and circular material flows that will reduce waste and promote recycling of materials.

The Blue Economy consists of sectors whose returns are linked to the living “renewable” resources of the oceans (such as fisheries) as well as those related to non-living and therefore “non renewable” resources (including extractive industries, such as dredging, seabed mining, and offshore oil and gas, when undertaken in a manner that does not cause irreversible damage to the ecosystem). It also includes activities relating to commerce and trade in and around the ocean, ocean monitoring and surveillance, coastal and marine area management, protection, and restoration. The following provides a summary of the types of activities or the components of a Blue Economy.

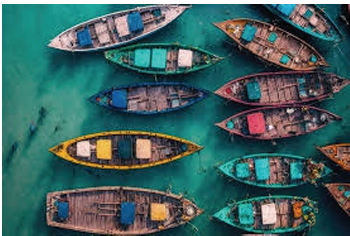

Fisheries

Fisheries

Demand for food and nutrition (seafood harvesting) has become a need for majority of the world’s population and has created a sub sector in the food and nutrition industry. The marine fishery is estimated to contribute USD 270 billion to the global GDP annually. Breaking it down, employment and other minor trade associated with fisheries also support a lot of livelihoods across the globe. A more sustainable fisheries industry can generate more revenue, more fish and help to restore fish stock. Sustainable fisheries can be an essential component of a prosperous Blue Economy, with marine fisheries contributing more than US$270 billion annually to global GDP (World Bank 2012). As a key source of economic growth and food security, marine fisheries provide livelihoods for the 300 million people involved in the sector and helps to meet the nutritional needs of the 3 billion people who rely on fish as an important source of animal protein, essential micronutrients, and omega-3 fatty acids (FAO 2016). The role of fisheries is particularly important in many of the world’s poorest communities, where fish is a critical source of protein, and the sector provides a social safety net. Women represent the majority in secondary activities related to marine fisheries and marine aquaculture, such as fish processing and marketing. In many places, employment opportunities have enabled young people to stay in their communities and have strengthened the economic viability of isolated areas, often enhancing the status of women in developing countries.

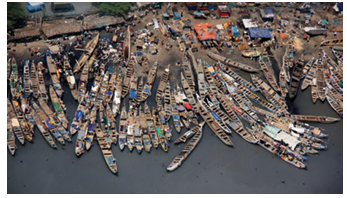

For billions around the world—many among the world ’ s poorest—healthy fisheries, the growing aquaculture sector, and inclusive trade mean more jobs, increased food security and well being, and resilience against climate change. All these are at risk from overcapacity, overfishing, unregulated development, and habitat degradation, driven largely by poverty and enabled by ineffective policy. Based on FAO’s analysis of assessed commercial fish stocks, the share within biologically sustainable levels decreased from 90 percent in 1974 to 68.6 percent in 2013. Thus, 31.4 percent of fish stocks were estimated as fished at a biologically unsustainable level and therefore overfished (FAO 2016).

For billions around the world—many among the world ’ s poorest—healthy fisheries, the growing aquaculture sector, and inclusive trade mean more jobs, increased food security and well being, and resilience against climate change. All these are at risk from overcapacity, overfishing, unregulated development, and habitat degradation, driven largely by poverty and enabled by ineffective policy. Based on FAO’s analysis of assessed commercial fish stocks, the share within biologically sustainable levels decreased from 90 percent in 1974 to 68.6 percent in 2013. Thus, 31.4 percent of fish stocks were estimated as fished at a biologically unsustainable level and therefore overfished (FAO 2016).

Marine Tourism

Tourism has been one of the largest industries in the world and has over a period contributed trillions of US dollars to the global economy and supporting the livelihoods of an estimated one in ten (10) people worldwide. On the global front, tourism is appropriately viewed as an engine of economic growth, and a pathway for improving the f or tunes of people and communities that might otherwise struggle to grow and prosper. Coastal and marine tourism represent a significant share of the tourism industry and forms an important component of the growing, sustainable Blue Economy, supporting more than 6.5 million jobs—second only to industrial fishing. With anticipated global growth rates of more than 3.5%, coastal and marine tourism is projected to become the largest value-adding segment of the ocean economy by 2030, at 26%. (World Bank, 2019). The Caribbean, which is strongly dependent on tourism for their economic growth and well-being, as well as other regions like Southeast Asia, are likely to benefit from this growth, particularly as more people in places like China and elsewhere have the means to travel abroad. Managing this growth well to ensure that the ecosystems that underpin tourism opportunities are sustained is going to be a key challenge. Capitalizing on this potential of the ocean will require a deliberate approach to shaping investment , through interventions like marine spatial planning, well-designed and funded marine managed areas, and new tools that help local communities and national governments alike to make the best long-term decisions possible.

Nature is the foundation of the world’s tourism today. Travelers are willing to pay a premium for a room with an ocean view, and words like “pristine,” “remote,” and “unspoiled” are frequently assigned to amenities like beaches, coral reefs, and panoramic seascapes. The dependency of the travel and tourism industry on a healthy environment goes much deeper than that, however, not only does a reef provide entertainment value for seaside visitors, but it can also deflect waves that cause erosion and reduces the risk of storm surges that can harm the industry’s bottom line. Clearly, nature contributes enormous value to tourism and other industries. But one of the challenges is knowing exactly where these benefits are produced in the first place. This knowledge can enable smarter investments in management and conservation actions that support both nature and the tourism businesses that support coastal economies.

Nature is the foundation of the world’s tourism today. Travelers are willing to pay a premium for a room with an ocean view, and words like “pristine,” “remote,” and “unspoiled” are frequently assigned to amenities like beaches, coral reefs, and panoramic seascapes. The dependency of the travel and tourism industry on a healthy environment goes much deeper than that, however, not only does a reef provide entertainment value for seaside visitors, but it can also deflect waves that cause erosion and reduces the risk of storm surges that can harm the industry’s bottom line. Clearly, nature contributes enormous value to tourism and other industries. But one of the challenges is knowing exactly where these benefits are produced in the first place. This knowledge can enable smarter investments in management and conservation actions that support both nature and the tourism businesses that support coastal economies.

The Nature Conservancy joined forces with the World Bank and other development partners to create the Mapping Ocean Wealth (MOW) initiative, which p rovides exactly such information. A new MOW study published in the Journal of Marine Policy reveals that seventy (70) million trips are supported by the world’s coral reefs each year, making these reefs a powerful engine for tourism. In total, coral reefs represent an astonishing $36 billion a year in economic value to the world of which $19billion represents actual “on-reef” tourism like diving, snorkeling, glass-bottom boating and wildlife watching on reefs themselves. The other $16 billion comes from “reef adjacent” tourism, which encompasses everything from enjoying beautiful views and beaches, to local seafood, paddle boarding and other activities that are afforded by the sheltering effect of adjacent reefs. The impact of this new information is already being r ecognized. MOW data prominently featured in a recently published World Bank report, “Toward a Blue Economy: A Promise for Sustainable Growth in the Caribbean” and in so doing, has helped to shape new policy and investments across the region. Last month, MOW received the “2017 Tourism for Tomorrow Innovation Award” from the World Travel and Tourism Council. In fact, there are more than seventy (70) countries and territories across the world that have million-dollar reefs, that generate more than one million US dollars (US$1m) per square kilometer.

These reefs support businesses and people in the Florida Keys, Bahamas and across the Caribbean, Mexico, Indonesia, Australia, Maldives and Mauritius, to name a few. This knowledge matters, not just for the tourism industry, but for conservation, too. The adage goes, ‘you can’t manage what you can’t measure.’ Armed with concrete information about the value of these important natural assets, the tourism industry can start to make more informed decisions about the management and conservation of the reefs they depend on, and thus become powerful allies in the conservation movement.

These reefs support businesses and people in the Florida Keys, Bahamas and across the Caribbean, Mexico, Indonesia, Australia, Maldives and Mauritius, to name a few. This knowledge matters, not just for the tourism industry, but for conservation, too. The adage goes, ‘you can’t manage what you can’t measure.’ Armed with concrete information about the value of these important natural assets, the tourism industry can start to make more informed decisions about the management and conservation of the reefs they depend on, and thus become powerful allies in the conservation movement.

Maritime Transport

Globally, shipping provides the principal mode of transport for the supply of raw materials, consumer goods, essential foodstuffs, and energy. It is thus a prime facilitator of global trade and contributor to economic growth including employment, both at sea and ashore. Shipping is the cheapest mode of transport, and carries 80% of the global merchandise trade in volume. In 2015, shipping transported ten (10) billion tons of merchandise for the first time (UNCTAD). UNCTAD expects world gross domestic products to decline further however, merchandise trade volume remained steady and as a result shipping becomes more i mportant as a means of transport for countries that are b e c oming popular in merchandise products. In this area, developing countries can play a great role and can get distinct benefits offered by the Blue Economy concept.

Some estimates indicate that international seaborne trade volumes can be expected to double by 2030 (QinetiQ, Lloyd’s Register, and Strathclyde University 2013) while, according to the International Transport Forum, port volumes are projected to quadruple by 2050 (ITF 2015). The impact of climate change (such as sea-level rise, increasing temperatures, and more frequent and/or intense storms) pose serious threats to vital transport infrastructure, services, and operations, and calls for better understanding of t he underlying risks and vulnerabilities, and the need to develop adequate adaptation measures. Given the strategic role of ports in the globalized trading system, developing measures for ports to adapt to the impact of climate change and to build their resilience is an urgent imperative. Benefitting from the economic opportunities arising from the oceans, including trade, tourism, and fisheries requires investment in transport infrastructure and services, and transport policy measures in support of shipping. It also requires efforts to address inter island/domestic/international Shipping connectivity. This includes incorporation into the broader regional and international maritime transport connectivity and access agenda.

The main environmental impact associated with maritime transport include marine and atmospheric pollution, marine litter , underwater noise, and the introduction and spread of invasive s p e c i e s . New international regulations require the shipping industry to invest significantly in e n v i r o n m e n t a l technologies, covering i s s u e s such as emissions, waste, and b a l l a s t w a t e r treatment. Some of the investments are not only beneficial for the 06 OCTOBER – DECEMBER, 2023 environment, but they may also lead to longer-term cost savings and mostly sustainable economic benefits for the future. Waste Management The sustainability of waste management in the marine industry in general has an equal potential of boosting the economic benefits derived for global purpose. It is therefore important to recognize the magnitude of the threat marine waste poses to the already established benefits. Most of the marine litter originates from land-based sources, while the remaining comes from sea-based sources such as maritime transport, fishing, and industrial exploration. It has been noted that plastics typically constitute the most important part of marine litter, sometimes accounting for up to 100 percent of floating litter (Galgani, Hanke, and Maes 2015). The impact of marine l itter include entanglement of and ingestion by marine animals, which have been identified as a global problem (United Nations 2016). Overall, marine litter affects economies, ecosystems, animal welfare, and human health worldwide. The disposal of hazardous chemical waste related to agriculture and manufacturing poses another challenge, as some Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and coastal Landlocked Developing Countries (LDCs) lack adequate facilities for storage and disposal. SIDS and coastal LDCs are also faced with the concern of transboundary waste from the effluent of cruise ships in their ports, as well as ships transiting through their national waters. The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal is an international instrument through which SIDS and coastal LDCs can seek to manage transboundary waste (UN DESA 2014b). There is a myriad of other ocean-related business ventures, including some that can contribute to the development of a Blue Economy. These can include activities such as re-purposing plastic debris collected from the marine and coastal environment into products and art, as well as other innovative activities.

The main environmental impact associated with maritime transport include marine and atmospheric pollution, marine litter , underwater noise, and the introduction and spread of invasive s p e c i e s . New international regulations require the shipping industry to invest significantly in e n v i r o n m e n t a l technologies, covering i s s u e s such as emissions, waste, and b a l l a s t w a t e r treatment. Some of the investments are not only beneficial for the 06 OCTOBER – DECEMBER, 2023 environment, but they may also lead to longer-term cost savings and mostly sustainable economic benefits for the future. Waste Management The sustainability of waste management in the marine industry in general has an equal potential of boosting the economic benefits derived for global purpose. It is therefore important to recognize the magnitude of the threat marine waste poses to the already established benefits. Most of the marine litter originates from land-based sources, while the remaining comes from sea-based sources such as maritime transport, fishing, and industrial exploration. It has been noted that plastics typically constitute the most important part of marine litter, sometimes accounting for up to 100 percent of floating litter (Galgani, Hanke, and Maes 2015). The impact of marine l itter include entanglement of and ingestion by marine animals, which have been identified as a global problem (United Nations 2016). Overall, marine litter affects economies, ecosystems, animal welfare, and human health worldwide. The disposal of hazardous chemical waste related to agriculture and manufacturing poses another challenge, as some Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and coastal Landlocked Developing Countries (LDCs) lack adequate facilities for storage and disposal. SIDS and coastal LDCs are also faced with the concern of transboundary waste from the effluent of cruise ships in their ports, as well as ships transiting through their national waters. The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal is an international instrument through which SIDS and coastal LDCs can seek to manage transboundary waste (UN DESA 2014b). There is a myriad of other ocean-related business ventures, including some that can contribute to the development of a Blue Economy. These can include activities such as re-purposing plastic debris collected from the marine and coastal environment into products and art, as well as other innovative activities.

Climate Change

Climate Change

The impact of climate change on t h e ocean and marine ecosystems profoundly affect human livelihoods and mobility. Recognizing the need to respond to the challenges arising from the interaction between ocean and marine ecosystem change, and h uman migration and displacement, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the Ocean and Climate Platform (OCP) are working together to bring visibility to this issue and promote concrete action to address these challenges. The impact of climate change on the ocean like the rise in sea level and coastal erosion. Changes the ocean current patterns and acidification is on the rise. At the same time, the ocean is an important carbon sink and, in a way, help to mitigate climate change.

Extractive Industries, Energy and Mineral

Energy is the mother of all economic development. The supremacy for controlling the sources of energy so far has i nfluenced the world’s geopolitics and therefore the suffering of humanity, human basic living and social i n tegration. Present worldwide average per capita energy consumption is very low and is even lower in least developed and developing countries. The high price of energy is to a great extent due to the dependency on the depleting natural hydro energy resources. Alternative sources of energy, especially renewable sources, have become the cry of the day. The Blue Economy Concept, among others, has brought forward the sea as the source of enormous quantum of energy. Mass quantities of extractable energy can be derived from the sea water mass by using the temperature gradient and waves. There are many more types, like wind energy and chemical energy that can be collected from the sea. Offshore oil and gas exploration and exploitation are already under way off the coasts of many states around the world, and much has already been learned about the need to manage the risks these activities generate as well as measures that can be taken to alleviate their impact. It is ultimately up to the coastal precedence over the needs and livelihoods of local fishing communities. This has led to a decline in the traditional fishing industry, as well as a decrease in the access to fishing grounds and resources for small-scale fisher folks. Balancing the needs of both the tourism sector and the local fishing communities is crucial to ensure sustainable development and equitable use of ocean resources. Other challenges include states to weigh the trade-offs between these potentially lucrative activities and the extent to which they preclude other uses of marine resources, including the sustainable exploitation of marine living resources. In contrast, the situation lacks clarity with regards to the exploitation of offshore mineral resources. To meet the growing d e m a n d f o r m i n e r a l s , momentum from both national governments and the private s e c to r ha s c a t a l y z ed the development of deep-seabed mining. A clear distinction must be made between minerals extraction under national jurisdiction, within the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of coastal states, and potentially beyond national jurisdiction, in the so called Area, as clearly laid out under UNCLOS, and under the premises of the International Seabed Authority (ISA)

The Challenges

For a considerable part of human history, the ocean has often been viewed as a source of unlimited r esources with limitless capabilities. These resources, however, are far from limitless, and the world is increasingly seeing the impact of the depletion caused by human activities in the ocean. The unchecked activities from various sectors and the consequent increasing adverse climate change has become a social and economic problem which must be tackled. Rising demand, ineffective governance i nstitutions, inadequate e c onomic incentives, technological advances, lack of or inadequate capacities, lack of full implementation of UNCLOS and other legal instruments, and i nsufficient application of management tools have often led to poorly regulated activities. These activities in turn have resulted in excessive use and, even, irreversible change of valuable marine resources and coastal areas. The increasing competitive space has marginalized small scale fisher folks, often vulnerable due to the rising dominance of the coastal tourism sector. As tourism continues to grow, it often takes precedence over the needs and livelihoods of local fishing communities. This has led to a decline in the traditional fishing industry, as well as a decrease in the access to fishing grounds and resources for small-scale fisher folks. Balancing the needs of both the tourism sector and the local fishing communities is crucial to ensure sustainable development and equitable use of ocean resources. Other challenges include; Ÿ Unsustainable extraction from marine resources, such as unsustainable fishing as a result of t e c h n o l o g i c a l improvements coupled with poorly managed access to fish stocks and rising demand. FAO e s t i m a t e s t h a t approximately 57 percent of fish stocks are fully exploited, and another 30 percent are over exploited, depleted, or recovering (FAO 2016). Fish stocks are further exploited by illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. Ÿ Physical alterations and destruction of marine and coastal habitats and landscapes due largely to coastal development, deforestation, and mining. Ÿ Coastal erosion also destroys infrastructure and livelihoods.

Marine pollution, for example in the form of excess nutrients from untreated sewerage, agricultural runoff, and marine debris such as plastics. Ÿ Impacts of climate change, for example in the form of both slow onset events like sea l evel rise and more intense and frequent weather events. Ÿ Unfair trade and border disputes.

Marine pollution, for example in the form of excess nutrients from untreated sewerage, agricultural runoff, and marine debris such as plastics. Ÿ Impacts of climate change, for example in the form of both slow onset events like sea l evel rise and more intense and frequent weather events. Ÿ Unfair trade and border disputes.

Sustainable Blue Economy

On 28th November 2018, Kenya and its co-hosts Canada and Japan invited the world to Nairobi for the first global conference on a sustainable Blue Economy. Over 18,000 participants from around the world met to learn how to build a Blue Economy expected to; Ÿ harness the potential of the ocean, sea, lakes and rivers to improve the lives of all, particularly people in developing states, women, youth, and Indigenous people. Ÿ leverage the latest innovations, scientific advancements, and best p r a c t i c e s t o b u i l d p r o s p e r i t y while conserving our waters for future generations.

The Conference concluded with hundreds of pledges to advance a sustainable Blue Economy, including 62 concrete commitments related to: marine protection; plastics and waste management; maritime safety and security; fisheries development; financing; infrastructure; biodiversity and climate change; technical assistance and capacity building; private sector support; and partnerships. The messages from the meeting were captured in the ‘Nairobi Statement of Intent on Advancing the Global Sustainable Blue Economy.” In addition, participants were invited to announce, “Leaders’ Commitments,” which resulted in pledges including:

- Marine protection: €40.million to protect corals and reefs and €60 million for the protection of marine areas in African countries by the European Union

- Plastics and waste management: US$100 million earmarked for b e t t e r o c e a n s management and against dumping, and US$200 million over the next four years for the development of initiatives to combat marine litter and microplastics (Norway)

- Maritime safety and security: €250 million for naval vessel replacement and the purchase of two marine patrol aircrafts (Ireland);

- Fisheries development: €40 million to support aquaculture value chains i n African countries (African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States, EU).

- Infrastructure: 600 projects leading to an investment of US$120 billion (India – Sagarmala Programme)

- Biodiversity and climate change: a US$10 million investment in the Pacific Initiative for Biodiversity, Climate Change and Resilience (Canada, together with the EU, New Zealand and Australia);

- Technical assistance and capacity building: US$20 million in increased technical assistance and capacity development in small island developing States (Canada).

- Private sector support: US$150 million by the Government of Canada and the private sector to build a knowledge-based ocean economy.

The Ghanaian Perspective

The concept of a sustainable Blue Economy has brought many economic prospects which nations may consider. The ocean is estimated to be worth about 1.3 trillion Euros and the figure is expected to double by the year 2030. Renewable energy, tourism, marine transport, aquaculture and fisheries, and many other sectors in the Blue Economy hold many untapped capacities especially in developing countries like Ghana. As a nation there is the need to educate and train people on the concept, its sustainability and the benefits to catalyze our success at making full use of it. The nation needs to implement, advocate, and promote “Blue Policies” that will bring about wealth creation and prosperity for the people. Some of the sectors in the marine industry have already yielded significant benefits and must be improved. Other areas within the industry need a holistic approach to doing things to yield not only economic benefits, but also sustain marine life and their environment. Ghana is blessed with a lot of resources including the ocean, coastal lands, lakes and dams, streams and rivers and many others which when put to prudent use will benefit the larger society. To achieve the desired benefits of its Blue Economy, Ghana needs a comprehensive Blue Economy strategy that is underpinned by a robust regulatory, legal, and institutional framework.

The Way Forward

Nations should effectively regulate fish harvesting. Overfishing, illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing and destructive fishing practices must end. Instead, science based management plans must be implemented to restore fish stock in the shortest time feasible, at least to levels that c an produce maximum sustainable yield as determined b y t h e i r b i o l o g i c a l characteristics. Nations must prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, from land based activities including marine debris and nutrient pollution. Additionally, the following must be pursued;

- Improve implementation of shipping regulations to r educe sea-based pollution

- Improve management of ballast water, biofouling, and other transportation r elated vectors of invasive species to improve overall resilience of marine and coastal ecosystems.

- Implement more sustainable and low carbon transportation systems globally to necessitate both capacity building and technology transfer.

- Implement international law pertaining to the conservation and sustainable use of the ocean and its resources, including, shipping.

Nations must take steps to prohibit certain forms of fisheries subsidies which contribute to overcapacity, overfishing, illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. Appropriate and effective differential treatment for developing and least developed countries should be an integral part of the World Trade Organization’s fisheries subsidies negotiation.

Conclusion

The Blue Economy concept can play a major role in Africa’s structural transformation, sustainable economic progress, and social development. The largest sectors of the current African aquatic and ocean-based economies are fisheries, aquaculture, tourism, transport, ports, coastal mining, and energy. Implementation of the United Nation’s policy on Blue Economy will help expand these s e c t o r s and address developmental issues in the wealth creation and prosperity.

By: Abdul Haki Bashiru-Dine, Ghana Shippers’ Authority